The charms of rural France in early September are many – rainy mornings giving way to sunny afternoons. Up and down gentle rolling hills appear field upon field of the three primary crops. Each farm seems to produce all three - corn for cattle fodder, sunflowers for oil and vineyards for wine – which define the essence of good French food. At this time of year many of the cornfields are harvested although an equal number remain drying in the warm sun. Sunflowers too have begun to be harvested, although most fields are at the dry-flower-still-on-stalk stage; a very few still sport sunny yellow flowers waving in the wind, suggesting possibilities of multiple growing seasons within the summer. And the vines are still pregnant with lush grapes, awaiting harvest within a month. Occasionally nestled among the acres of the primary crops are small patches of family tomato plants, the tomatoes bright red and standing out like beacons.

For seven days with long-time British friends I roamed stretches of western France, beginning in Giverny, moving to Mont S-Michele and thence to country north of Bordeaux where we visited forts (Chinon) and castles and gardens (Chenonceau), and lovely small towns and villages each offering their own charms and revealing their individual histories (Dinan, Mortagne, Brouges, Talmont, Pons, Cognac). Europe’s largest estuary, the Gironde, had a number of small towns and harbors offering restaurants for companionable meals, featuring the area's specialty of moulins, vistas for viewing and boats whose rigging chimed gently in the wind. One fascinating aspect was to read about the close relationship between England and the towns and sites we visited. As Americans we are so accustomed to our long-standing connections with England that to see the much longer inter-relationships beginning long before the Norman conquest of England in 1066 is humbling.

Giverny, most famous as inspiration for Claude Monet, could not fail. We reached the park in the late afternoon under cloudy skies that held their rain until we left. The garden, a few images here, displayed strikingly beautiful plants, walkways past the streams and poplars and wonderful vistas of the lily ponds. The house we wandered through offered his home as well as the views Monet had of the garden in front of him.

The next morning the approach to Mont S-Michel reminded me of my initial thoughts when I turned a corner in Cairo some 20 years ago and saw a pyramid, “this is supposed to be in books!” The sign as we parked the car reminded us that our vehicle would be underwater by 6:30 pm. Clearly the sign is changed twice a day.

Physically, Mont Saint-Michele is a sheer-sided rock rising 250 feet out of the water surrounded by one of the strongest tides in the world. The land around the rock is extremely flat and the tides come in over a dozen miles in a space of a few hours. Originally the Mont was a place for devout Christians to live as hermits in solitude. The early monks were rebuked for their immoral and impious behavior by Duke Richard and thrown out and replaced in 966 with submissive and humble monks from Flanders. They adopted the principles of Saint Benedict and the abbey became a Benedictine abbey. The end of the hundred years’ war left Normandy in the hands of the English who subsequently laid siege to the Mont. The siege was to fail and the citadel did not fall, bolstering the confidence of the French. The French Revolution caused the monks to scatter leaving the abbey to be used as a prison. The abbey was rediscovered in the 19th century by writers and visitors and established as an historic monument in 1874. It has been renovated and restored to its use as a religious center and after the celebration in 1966, celebrating it 1000-year history, again came under control of the Benedictines.

We roamed Mont Saint-Michel entering through the Forward Gate, the Boulevard gate and the King’s Gate into the small Norman village at the foot of the abbey.

The main street of the town leads to the abbey at the top of the rock via a great outer staircase. We walked to the entrance of the abbey pausing to take pictures from various parts of the ramparts and admire the strand laid out before us.

The main street of the town leads to the abbey at the top of the rock via a great outer staircase. We walked to the entrance of the abbey pausing to take pictures from various parts of the ramparts and admire the strand laid out before us.

Strikingly beautiful to me were the ever-changing views of the sea around us with moving and changing cloud patterns and birds wheeling from the mud flats to the sky.

We entered the abbey walking up to the gardens at the top.

We entered the abbey walking up to the gardens at the top. If there hadn’t been signs clearly showing us which way to go, I fear we would still be there as room after room resembled each other and the path through the abbey quite unclear. From the outside we could see what looked like an enormous ladder into a window high up.

If there hadn’t been signs clearly showing us which way to go, I fear we would still be there as room after room resembled each other and the path through the abbey quite unclear. From the outside we could see what looked like an enormous ladder into a window high up. From inside we could see that the apparatus was connected to an enormous wooden wheel inside, used as leverage to bring all manner of supplies to the abbey from the entrance to the town.

From inside we could see that the apparatus was connected to an enormous wooden wheel inside, used as leverage to bring all manner of supplies to the abbey from the entrance to the town.From our hotel some few kilometers away, we saw the Mont from a distance and roamed the ‘beach’ between our hotel and the Mont. The singular reason I could see to stay in one of the hotels within Mont S-Michel would be to experience the Mont completely surrounded by water, reason enough if you don’t mind lugging baggage by hand up some steep streets.

Our next stop was the town of Dinan, whose prosperity began in the 11th century, on the river Rance connecting the town to the sea. Traders and craftsman formed the heart of their prosperity. Dinan was under siege by the English in the 14th century. Religious orders, Dominican monks and Ursuline nuns, were attracted to Dinan and by the 18th century it was a wealthy town whose cloth and leather manufacturers, fairs and markets ensured it prosperity. A railway in 1879 opened the town to its first tourists. We were simply continuing this trend as we visited on market day. The town had many charms, from the Clock tower to the boats moored along the river, the church that traces its history back to the crusades, and the winding streets in the area around the clock tower.

Leaving Dinan, we drove to our next reserved hotel, the Manoir de la Giraudiere where we had intended to stay two nights, visiting the sites in the neighborhood. A disappointing dinner and no hot water in the morning urged us on to stay an extra night in my friends’ place in Champagnolles. Before we arrived late in the afternoon, we went from rain (at Chinon) to lovely sunshine at Chenonceau.

The Royal Fortress of Chinon, situated at the crossroads of three provinces (Anjou, Poitou and Touraine) is currently heavily under reconstruction but we could enter the Fortress through an underground passage used by Charles VII as a concealed exit when he visited his mistress Agnes Sorel. The Counts of Blois who first built Chinon, ceded it to the Counts of Anjou in 1044 whose most famous count, Henry Plantagenet, became King of England in 1154. The main place we visited, after touring the grounds in a gentle rain, was the Clock Tower, built on 12th century foundations with upper part rebuild in the 14th c. Today it houses a museum dedicated to Joan of Arc. It was at Chinon that the Maid met the Dauphine and quick search from Google for Joan d’Arc and Chinon brings up a wealth of information. From the ramparts and views from the rooms in the Clock Tower, we can see the lovely river to one side and vineyards to the other. With the river at our back and the vineyards ahead, to our right are the remains of the Saint-Georges Fort, an area currently under excavation/renovation on which was probably constructed a palace by Plantagenet King Henry II. It was fortified at the end of the 12th century during the conflicts between Richard he Lionheart and then John Lackland, and Philip Augustus. Today it is under some reconstruction and the new reception area will be built in front of the fort.

From the Fortress of Chinon we drove through gradually lightening skies to Chenonceau, a chateau on the Cher River built in the 16th c. when the castle-keep and the fortified mill of the Marques family were razed. The tower alone was kept and rebuilt in Renaissance style. Most of the rooms of the Chateau have been reconstructed and furnished with period pieces. Many rooms follow their original use, others have been used to portray the living space and materials of one of the former inhabitants. Stories of the those occupying this chateau during its hundreds of years history abound. Most interesting to me was the story and room of Diane de Potiers (1499-1566), mistress of the French King Henry II, to whom he gave Chenonceau. She was the wife of the grand seneschal of France, Louis de Breze, duchess of Valentinois, and a lady-in-waiting to the Queen. She is said to have combined great beauty with intelligence and a flair for business, exceptional for the time. The Chateau was given to her in 1547 by Henry II as a gift in recognition of the services rendered by her husband to the Crown, apparently a common strategy. She set about running the Chateau in a model that stands today. First she drew up a list of all properties involved, developed a team of advisers and set about making it a profitable business. Besides carrying out interior and exterior renovations, she laid out gardens that were among the most modern and spectacular of the times; carefuly constructed replacements are there today.

In 1599, Henry II was killed in single combat during a tournament. His widow, Catherine de Medicis, ordered Diane to give Chenonceau back to her and in return she gave her the chateau of Chaumont-sur-Loire. The ceiling of the green study, beside the bedroom of Diane, carries today the pattern of intertwined ‘C’s. It was from this study that Catherine, who became Regent of the kingdom when Henry II died, ruled France.

The following day, after settling into the small town of Champagnolles for a few nights, we drove to the near-by Gironde Estuary, the largest in Europe. Since estuaries are semi-enclosed coastal bodies of water with one or more rivers or streams flowing into them, and flowing on to the open sea, there is little if any wave action and they provide excellent breeding grounds for a wide variety plants and animals. Although they are often associated with high levels of biological diversity, they are also endangered today by pollution and other man-made woes. We lunched in a lovely restaurant just a few steps from the inland slip at Mortagne, home to dozens of sailing vessels at the end of one of the rivers flowing into the Gironde.

The following day we drove to Brouage, a medieval town whose origins go back at least as far as the Gallo-Roman era when it was a gulf, 15 km long by 10 km wide. The dropping of the sea level and alluvial deposits made with each tide gradually filled in the gulf. From the beach there developed a zone of salt marshes which became salt-pans and a major medieval industry was born. Abbey documents reveal a very active commerce in salt, supporting people who worked the salt pans, to middle men and revenues, via taxes, to the clergy, nobility and the king. Brouage salt (including all salt from the Marennes-Oleron basin) had an international reputation. The importance of salt in preserving foods, tanning hides and medicinal purposes was vital from prehistoric times until far later when industrial developments provided alternatives for salt. We saw its importance on the small island of Ustica off Sicily whose middle bronze age village we excavated in the 1990s. There the evidence came from singular pans whose thin flat bottoms and sturdy low walls were placed in the sun and besides fires to evaporate the water from the sea water. Returning to Brouage, it is well recorded that boats were filled with Brouage salt in the early 17th century and sailed to Newfoundland for cod fishing. Records indicate that it was a common sight to see 200 ships clustered together for security and in 1649 over 1700ships left Brouage with salt bound for the countries in Europe and surrounding the Baltic Sea.

With this level of commerce it is easy to see that a major town was developed, perhaps one of the first prototypical planned villages, whose first inhabitants chose the best sites, nearest the port. The planned town was built in 1555 to follow the geometric plan it retains to this day. The fortifications were not part of the original plan but necessitated by a variety of wars, including the wars of religion. It is possible to walk easily along many parts of the ramparts and observe the oyster farms (replacing the salt industry), the wonderful fields rich with wildlife, and to eat in any number of fine bistros.

After Brouage we visited more of the Marennes Basin west of Brouage and drove the viaduct to Oléron Island, passing Fort Boyard, a splendid "stone ship" built in the ocean, which, like Mont S-Michele is completely surrounded by tidal water some parts of the day. One of the leading characteristics of the Marennes Basin and Oléron Island is the unspoiled landscape that covers over 12% of the island with large forests and marshes. Nature conservation areas are open year round and migratory birds find a natural haven here. Oléron Island has an area of 175 sq km, making it the largest French island of the Atlantic coast. Visit their web site (www.oleron-island.com)to see much more.

Our final stop of the day was Talmont, a very small village, with low attractive whitewashed houses, 15 km south-east of Royan, in Poitou Charentes. The village is on a promontory in the Gironde Estuary, at whose head is a lovely 11th century church, built in the Roman style, and surrounded by a small cemetery. The views along the coast from the cemetery are spectacular, of high white cliffs in both directions.

On our final day we visited Pons, which became an English possession in 1152 when Eleanor of Aquitaine married Henry II (you may recall his mistress Diane from Chenonceau). Possession of Pons reverted to the French and then in 1259 back to an English possession once again. In the 14th c the Lords of Pons were at their strongest and in 1621 Louis XIII conquered Pons and his troops destroyed all the military equipment of the fortress except the tower. As the guide page states, “From this date, the Lords of Pons saw all their powers disappear and the historical importance of the town became negligible.”

One cannot leave Pons without however reflecting on their role and the pilgrims’ hospital in the pilgrimage of Compostela. From the backcover of the guide we read that “At the dawn of the 9th century a star appeared in the skies above Galicia. It led to the discovery of the tomb of James the Great, the apostle of Christ. In the 12th century, the Field of the Star became Campostela, one of the three great centres for pilgrimages in Christendom together with Rome and Jerusalem. Pilgrims came from all over Europe, following four main routes which cross France and join to become one at Puente la Reina: Camino frances. On these routes, churches, hospitals, abbeys, bridges, medieval village and towns tell the story of these walkers of god which was written and is still being written, on the roads to Campostela.” We visited the hospital at which travelers to Campostela from Tours would stop. A chart from 1330 refers to it as ‘the most peaceful and honest place on the hedge of the town of Pons which is also honest, good and peaceful.’ Geoffrey III, Lord of Pons, ordered its construction ‘to salve his soul, those of his parents and to help the poor.’ Today the 12th c ribbed vault, the last remaining in France, incorporates a large display of photographs and discussion of the pilgrimage and the hospital. A recent addition of a medieval herb garden offers a lovely respite to wander and sit.

Cognac was the last town to visit and we wandered through the streets, to the river and briefly watched a film crew beginning to address the church for its needs. Situated on the river Charente between the towns of Angoulême and Saintes, the majority of the town has been built on the river's left bank, with the smaller right bank area known as the Saint Jacques district. Unknown prior to the 9th century, the town was subsequently fortified. Francis I granted the town the right to trade salt along the river, guaranteeing strong commercial success, which in turn led to the town's development as a centre of wine and later brandy. Cognac, like Pons, is on the pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostella.

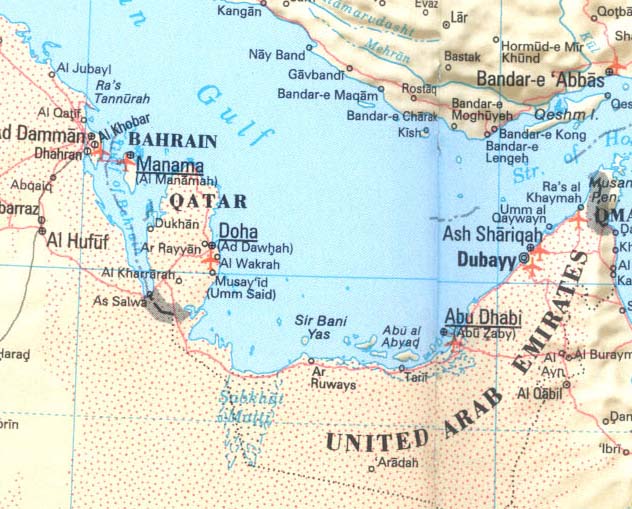

The next day I flew from Bordeaux to Paris and thence to Doha.