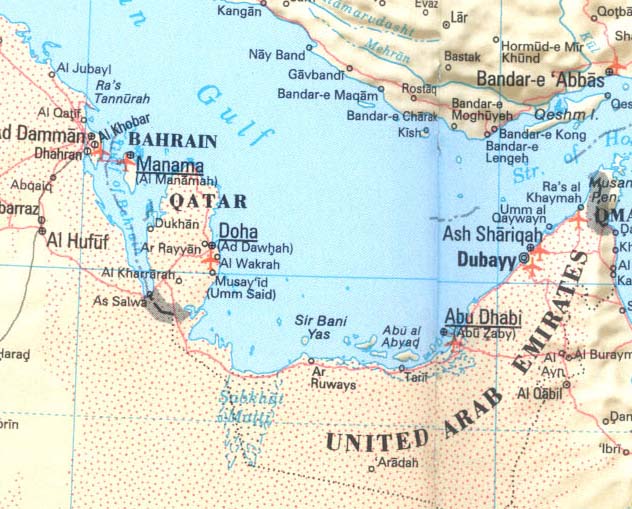

The jolt of pleasure shouldn’t have surprised me when I awoke in Muscat recently and saw the mountains in the bright sunlight outside my room - how much I have missed mountains in this flat sandy peninsula of Qatar that I now inhabit. During my brief visit to Oman the enjoyment persisted, driving through mountains, over mountains and inside mountains, as my Arab driver repeatedly referred to places and villages: ‘inside the mountain’ is not to be taken as literally within the earth but as a place within the mountain range completely surrounded by mountains, as if a piece had been carved out. The mountains in Oman are raw and jagged with little if any plant growth. Perhaps they have only recently pushed themselves to the surface and are looking around to grasp the measure of the place they now dominate.

Growing up in New England, the largest mountain I encountered was Mt Washington and not insignificant especially in the howling winds of winter; it was however dutifully climbed in high school. It wasn’t until I spent a summer in southern Arizona during my undergraduate years and experienced the size and power and silence of the mountain range at the south, where one could, at least 40 years ago, gaze from the heights over miles of land stretching south into Mexico. I recall to this day the silence that accompanied the view, few birds and insects and no noises of civilizations. This was a silence akin to one I experienced in a vastly different setting along the Nile some twenty years later when, having left the sights and sounds of modern life behind, I felt I was as close to what the early Egyptians experienced as I could get as my boat silently slipped down the river with the bulrushes on either side. Somewhere during the following years I read Loren Eiseley’s The Immense Journey and was struck dumb by the following:

Once in a lifetime, perhaps, one escapes the actual confines of the flesh. Once in a lifetime, if one is lucky, one so merges with sunlight and air and running water that whole eons, the eons that mountains and deserts know, might pass in a single afternoon without discomfort.Mountains have accompanied my field work in southern Italy and Sicily: the Alburni mountains south of Salerno and west of our excavations at Tufariello served as a magnificent backdrop to our work; the majestic stone outcropping defined the essence of La Muculufa in central Sicily, under whose shadow we found remains of a village as well as a ceremonial site from 2000 BCE and, literally, in which burials had been placed and looted millennia before; the mountains east of Paestum, seen both from the Greek temples as well as from the hardscrabble site of Trentinara on their western edge from which one could easily watch with safety and ease the activities further west in the areas where the Greek temples would sprout 1500 years later; the ‘mountain’ on Ustica, merely the edge of the tipped caldera of a very ancient volcano, from which we could survey the entire small island; and mountains running across and up and down Sicily through which we travelled time and time again, through bright sunlight, silvery moonlight and glorious thunderstorms. The passes through the mountains and the mountains themselves have long provided safe havens as well as opportunities for travel. The people whose remains we excavated too may have wondered at the eons that mountains know and questioned who else had passed through or would. The evidence of commerce can be found in mountain passes but not all evidence of such passages can be readily interpreted. A few decades ago evidence from a cave in southern Italy prompted the following interpretation of mine:

Zinzulusa

ca. 1050 b.c.

He’d been travelling since dawn.

Now the heat rose from the fields below, here green sunlight and cool shadows,

Farther up, the shadows he sought, a refuge for his axes –

‘a scuri a occhio’, one handsomely decorated –

too fine to leave with those in the valley.

A quick climb then to the cave,

recesses stretching back in time as well.

A niche in the wall to the right, easily covered by rocks,

would conceal should someone enter the cave.

The depths of the grotto reached out, inviting cool darkness.

Safer perhaps back there?

No, time was short now, and he’d soon return.

(Pots, unseen in the shadows for a thousand years already, remained undisturbed.)

The darkness was a welcome respite to the hot bright outside.

But he’d lingered too long already.

One last look – yes, this cave would harbor his axes.

He stepped into the sunlight, out of the quiet toward the heat and strife below.

Zinzulusa

ca. 1980 a.d.

These things alone are known:

two bronze axes,

burnished pots from the depths of Zinzulusa

and Zinzulusa itself.

(1980)